NOTE: THIS ENTRY HAS BEEN SALVAGED FROM AN INTERNET CACHE AND REPOSTED UNEDITED ON 4/30/2008. SOME INFORMATION MAY BE OUTDATED, AND OUTGOING LINKS HAVE NOT BEEN INSPECTED FOR REPUBLICATION. UNFORTUNATELY, COMMENTS HAVE BEEN REMOVED AND ARE CLOSED.

* * * * *

Welcome to the Friz Freleng Blog-A-Thon, in celebration of the late animation master's

100th (or is it

101st, or

102nd?) birthday. The picture to the right is a caricature of Friz from the 1952 Chuck Jones cartoon

the Hasty Hare. Links to other sites participating in the occasion will be listed at the bottom of my long-winded post. Thanks to everyone for participating! I think it's wonderful to have such a collection of writings on Freleng in one place on the anniversary of his birth!

I'm not an animator or an animation scholar, but I love to watch classic cartoons, and sometimes try my hand writing about them. Knowing that writers far more practiced than I can sometimes get their extremities caught in painful, embarrassing traps when trying to reach for analysis of cinematic topics outside their realm of expertise (

Mick LaSalle being a recent example) might make me hesitant to write on the form. But, though I'm still in the beginning steps of understanding the animator's craft (a term I use because it parallels the commonly-used "actor's craft", not to imply that animating or acting are unartistic endeavors), I hope I have something to contribute to a discussion of cartoons, if only an expression of my passionate belief that the best are as essential as the acknowledged

great works of the cinema.

One of the film critics I most admire, Manny Farber, was among the first non-specialists to treat the Warner Studios' cartoons as an important topic of discussion, with a piece published September 20, 1943 in

The New Republic called "Short and Happy." It's a brief, six paragraph article, but it does a good job describing the amoral appeal of the Warner house style in the early 1940s when compared to the growing tendency of Disney (the only cartoon studio to have received widespread critical attention at that time) toward virtuous uplift. In 1941 Preston Sturges had made a similar, if perhaps unintended, critique of Disney's transformation by using scenes of pure slapstick from 1934's

Playful Pluto in his

Sullivan's Travels as the catalyst for the film director's conversion from would-be educator to entertainer, reversing Disney's path during the period. Farber praised Merrie Melodies for being "out to make you laugh, bluntly, and as it turns out, cold-bloodedly." The problem with his praise in the original article, however, is that it now seems rather misdirected. Repeatedly Farber gives the credit for the cartoons to the producer Leon Schlesinger and not any of the directors to whom we now know he gave relatively free creative reign. This is probably why, by the time "Short and Happy" was placed in the 1971 Farber collection

Negative Space, it had been edited to attribute the cartoons' singular qualities to Freleng, Tex Avery, Chuck Jones, and Robert McKimson. But the re-edit causes more problems than it solves, as by bringing McKimson into the equation Farber awkwardly conflates two eras of Merrie Melodie-making: 1940-42, when Jones, Freleng and Avery were directing but McKimson was still an animator, and the period that stretched from 1950 until the early 1960s, when nearly all the studio's cartoons were directed by Jones, Freleng or McKimson. An added paragraph constrasting the directors' styles feels like it belongs in a different piece; it was that paragraph's reference to the 1958 cartoon

Robin Hood Daffy that made me feel the need to look up old issues of The New Republic on microfilm.

Sad to say, Freleng probably emerges from Farber's 1971 (or earlier?) re-edit worse off than if he, like Robert Clampett or Frank Tashlin, hadn't been mentioned at all. In the new paragraph, Freleng is simply described as "the least contorting" while Avery gets to be called "a visual surrealist" and McKimson "a show-biz satirist", with Jones receiving several sentences of praise all to himself. At least Freleng cartoons like

the Fighting 69 1/2 and

Hiawatha's Rabbit Hunt get singled out for praise, but the latter is misidentified as a McKimson product in the re-edit. Perhaps the most enduring line Farber uses to describe the cartoons is: "The surprising facts about them are that the good ones are masterpieces and the bad ones aren't a total loss." In the original article three examples of "good ones" are identified as

The Case of the Missing Hare,

Inki and the Lion (both Jones) and

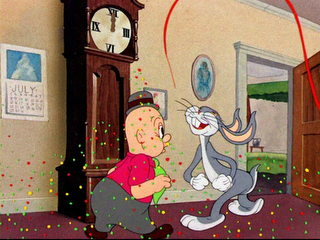

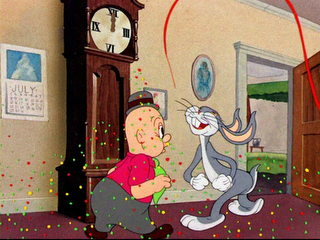

Hiawatha's Rabbit Hunt. But the lone counter-example is the "poor"

Wabbit Who Came to Supper which is saved by a single gag (where Bugs tricks Elmer into celebrating New Year's Eve in July) from implied "total loss"-hood. I disagree; that's one excellent 'toon!

But here I am, already on the fifth paragraph of this post, and I still haven't gotten around to saying what it is about Freleng that made me want to initiate this Blog-a-Thon in the first place. The above stuff is important, I think, because Farber is a deservedly influential critic, and his damningly faint praise of Freleng's talents in the revised "Short and Happy" has probably held some sway over the many, many readers of

Negative Space in the years since its publication. It, or other conventional wisdom like it, certainly held some sway over my own opinions of Warner cartoons when revisiting them as an auteurist-minded adult. I took the genius of Avery and Jones almost for granted, and it was Bob Clampett's extraordinarily distinctive (almost always MOST contorting) style that first caught my attention as something of a "new discovery" for me. But gradually I began to appreciate Freleng more as well, and now I think he among all the Termite Terrace directors most exemplified this original Farber quote, contrasting the studio's artistic method against "insipid realism":

It is a much simpler style of cartoon drawing, the animation is less profuse, the details fewer, and it allows for reaching the joke and accenting it much more quickly and directly: it also gets the form out of the impossible dilemma between realism and wacky humor.

Increased realism has been a constantly recurring ambition of animated and live-action filmmakers alike. The Warner cartoonists were not immune; most notably, Jones started his directing career attempting to draw simulations of the natural world in films like

Joe Glow the Firefly. Avery would often take a scene to the technological limit of cartoon realism, then demolish that limit with a gag drawing attention to the cinema-unreality of any filmed image (the hair-in-projector gag in

Aviation Vacation being a quintessential example.) Clampett, on the other hand, fought against tendencies toward cartoon realism, and usually ended up with an anything-goes cartoon universe of wackiness. What Freleng would do in his most effective cartoons was something else: he'd create a gag that, if not realistic, would at least be performed by his characters as it would be if they were vaudeville actors. Then he would repeat the gag to the point of ridiculousness, altering time and/or space to increase the impact of the humor, and creating a sense of inevitability that is funny in a completely different manner than the unpredictable hilarity of a Clampett cartoon.

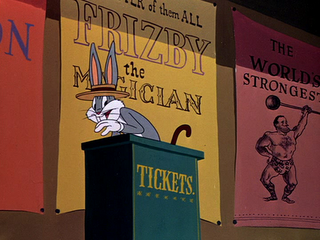

The Wabbit Who Came To Supper follows this pattern, as do many of the Sylvester-Tweety cartoons, but the most perfect distillation of the principle is probably the 1949 Yosemite Sam/Bugs Bunny face-off

High Diving Hare.

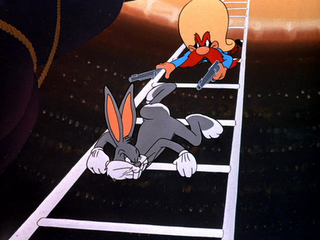

As Greg Ford notes in his commentary on the

Looney Tunes: Golden Collection disc on which this short appears,

High Diving Hare has a long set-up. It's true that there is often some gag-light "dead space" in a Freleng cartoon, but at least in the case of this one, the set-up is necessary to build the gag premise that will so pay off in the second half of the cartoon. The premise, for those of you who may not have seen the film before but want to see me overexplain it (I really don't recommend that; please watch it right now or skip to the end of this post where the links to other bloggers are) is that Bugs is presenting a variety show at an Old West Opry House. Yosemite Sam's favorite daredevil Fearless Freep is on the bill, inspiring the diminutive gunslinger to lay down a pile of cash and plop down right in front of the stage. Carl Stalling's musical contribution increases the tension as the camera makes a vertical pan (Paul Julian's background using a perspective effect to simulate a live-action tilt) up the impossibly high ladder to the platform Freep is going to dive off of. But if Sam isn't impatient enough already, he

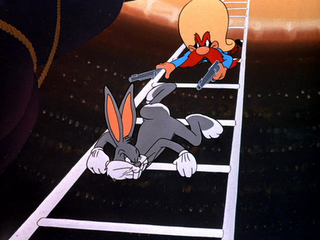

really loses his temper when Bugs interrupts a lengthy introduction to accept a telegram from the weather-delayed diver. Of course, all this set-up isn't to make Sam's anger more believable; with Yosemite you believe his anger from the first cel. It's to create a situation in which Sam doesn't want to just kill Bugs in his usual way, but to motivate him to force Bugs up the ladder to the platform so he'll dive in Freep's place. Freleng and his crew don't have a pair of six-shooters that can make Yosemite climb that ladder himself; they have to construct and draw everything.

The first dive takes over a minute to unfold, but each second is perfectly used. First there's the climb, backed by Stalling's chromatically-rising violins, then acrophobic (or so he says) Bugs inching to the edge of the diving board, then clinging to Sam and to the board to avoid the fall. When Sam aims his guns and orders, "now, ya varmint! dive!" it seems like the moment of no return. But of course it's really the perfect moment for a Bugs switcharoo. He convinces Sam to turn around and close his eyes while he puts on his bathing suit (an absolutely absurd modesty since Bugs is naked to begin with!) With his adversary not looking, he's able to rotate the board around an imaginary center, then use sound effects he must have learned from Treg Brown to bamboozle Sam into thinking he'd actually jumped into the bucket of water at the bottom of the ladder, when he's actually just landed on the platform, only a few feet lower than where he started. What happens next is absolutely priceless: Sam expresses genuine respect for the "critter", and in his state of shocked admiration he steps off the board into a stagebound freefall.

I'm not going to detail each of the subsequent 8 times Yosemite tries to force Bugs off the diving board and ends up the fall guy himself, but in each iteration of the gag the climb-trick-fall cycle gets briefer than the previous, except for the third, and the ninth and last fall. Sam's third ascent takes a few seconds longer because it's the film's first real break with the rules previously established in the cartoon's exaggerated but thus far logical universe. When he steps out on the board, unable to figure out where Bugs went, the audience is privy to the knowledge that he's standing upside-down on the underside of the board. Or so we think; as soon as Bugs informs Sam that

he's the one upside-down, he falls, illustrating the principle that Looney Tunes characters can do anything until they realize they've done something they can't. By falls number seven and eight Freleng leaves the camera trained on the middle of the ladder so that we see a sopping wet Sam climbing up, and soon enough falling down and making a splash, but we aren't shown what Bugs is doing up there to keep Sam's water wheel of torment turning. The moment when we expect to see him fall again, but instead the silence is broken by the sound of sawing, is a hilarious friction between anticipation and surprise. The resolution is perfect because it's simply too easy. When Michael Barrier in

Hollywood Cartoons claims that "gags in Freleng's cartoons tend to be of equal weight, so that a cartoon simply stops when its time is up" he either isn't considering

High Diving Hare or else he's thinking specifically of big, complicated, finishes like the ones Jones supplies in most of his Road Runner or Sam Sheepdog cartoons.

High Diving Hare's "biggest" gag is the first dive, and the others are like ripples on the surface, keeping the laughter generated from the initial splash going and going.

This is all just how I see it. Please feel free to disagree with any or all of my train of thought by leaving a comment below!

Freleng appreciators in the Frisco Bay area will want to know that the

Balboa Theatre will be holding a tribute to the director sometime this Fall, including a screening of Ford's 1994 documentary

Freleng Frame-By-Frame. (I'll post the precise date when I learn it through the theatre's informative weekly newsletter, available on the theatre

website and through e-mail.) In the meantime they're screening a (non-Freleng) cartoon before each showing of

Little Miss Sunshine.

Once again, thanks to all the participants in this Blog-A-Thon! If you've written something you'd like me to link, please

e-mail me or leave a comment. Here are the links I've collected so far; they'll be updated several times throughout the day:

Adam Koford at Ape Lad.

Akylea at Robots cry too (en Español / in Spanish).

alie at blogalie (en Español / in Spanish).

ASIFA-Hollywood.

Brad Luen at East Bay View.

Brendon Bouzard at My Five Year Plan.

Craig Phillips at Notes From Underdog.

Dave Mackey.

David Germain at david germain's blog.

Dennis Cozzalio at Sergio Leone and the Infield Fly Rule.

Dennis Hyer at Atlantic County Cartoons.

Gir at Gir's room with a moose.

girish.

Harry McCracken at Harry-Go-Round.

J.E. Daniels at the Adventures of J.E. Daniels.

Joe Campana.

Josh at jazz::animated.

Kurtis Findlay Burnaby at animated toast!

Michael Guillen at The Evening Class.

Mondoxíbaro (en galego / in Galician).

Peter Nellhaus at coffee, coffee, and more coffee.

Richard Hildreth at Supernatural, Perhaps -- Baloney, Perhaps Not.

Sean Gaffney.

Stephen Rowley at Rumours and Ruminations.

Steven at The Horror Blog.

Ted at Love and Hate Cartoons.

Thad Komorowski at Animation ID.

Thom at Film of the Year.

Tom Sito at Tom's Blog.

Xocolot (en Español / in Spanish).

UPDATE 8/22/06: Just wanted to point out that

Wade Sampson published a MousePlanet piece on Freleng last week in honor of the centennial as well.

Also, thanks to

Cartoon Brew,

Greencine Daily,

La Vanguardia and other sites that spread the word about the Blog-a-Thon. With more than two dozen officially participating sites, I'd call the day an unqualified success!

The "Classical Hollywood Style" of the 1930s and 40s is often referred to as if it were a monolith. The achievements of Hollywood auteurs from the era, whether Chaplin or Welles, Hawks or Hitchcock, are usually illustrated in terms of their divergence from this so-called "invisible style". Less often discussed are the contributions individual directors (outside of D.W. Griffith) may have made to constructing the style.

The "Classical Hollywood Style" of the 1930s and 40s is often referred to as if it were a monolith. The achievements of Hollywood auteurs from the era, whether Chaplin or Welles, Hawks or Hitchcock, are usually illustrated in terms of their divergence from this so-called "invisible style". Less often discussed are the contributions individual directors (outside of D.W. Griffith) may have made to constructing the style.  But it's also interesting to take a look at Borzage flourishes that did not become assimilated into the "Classical Hollywood Style." Take Man's Castle, a beautiful film in spite of an apparant technical crudity even for a film made at the low-budget Columbia of 1933. I say "in spite of", but is it in part because of certain now-crude-seeming characteristics that the film is such a masterpiece? Frederick Lamster, in his 1981 auteurist survey Souls Made Great Through Love and Adversity points out that after an early scene in which Spencer Tracy's Bill has just dramatically revealed his shared bond of poverty with the homeless Trina (Loretta Young, who developed a real-life romance with Tracy during filming), the couple are visually separated from the street crowd by a scale-distorting back-projection. The technical effect would be unacceptable by the standards of realism demanded for Hollywood product only a few years later, but the emotional effect of showing the pair all the more isolated from the world around them adds resonance to the film's romatic themes. I also noticed numerous instances in the film of what could be eyeline mismatch, but which also lent a dreamlike outlook to Borzage's starry-eyed characters.

But it's also interesting to take a look at Borzage flourishes that did not become assimilated into the "Classical Hollywood Style." Take Man's Castle, a beautiful film in spite of an apparant technical crudity even for a film made at the low-budget Columbia of 1933. I say "in spite of", but is it in part because of certain now-crude-seeming characteristics that the film is such a masterpiece? Frederick Lamster, in his 1981 auteurist survey Souls Made Great Through Love and Adversity points out that after an early scene in which Spencer Tracy's Bill has just dramatically revealed his shared bond of poverty with the homeless Trina (Loretta Young, who developed a real-life romance with Tracy during filming), the couple are visually separated from the street crowd by a scale-distorting back-projection. The technical effect would be unacceptable by the standards of realism demanded for Hollywood product only a few years later, but the emotional effect of showing the pair all the more isolated from the world around them adds resonance to the film's romatic themes. I also noticed numerous instances in the film of what could be eyeline mismatch, but which also lent a dreamlike outlook to Borzage's starry-eyed characters.