The Pacific Film Archive has its new calendar up. It's unsurprisingly packed with must-sees. As disappointing as it's been to learn that my neighborhood theatre the Balboa would in fact not be a venue for a Janus Films tribute this fall, knowing that the PFA is tackling two such series, one largely Europe-focused and the other Japanese is something of a balm. Just as enticing are the Jacques Rivette series, a set of Beat-era films, and a fascinating series guest-programmed by Akram Zaatari. And more. It almost makes me want to move to Berkeley.

The Pacific Film Archive has its new calendar up. It's unsurprisingly packed with must-sees. As disappointing as it's been to learn that my neighborhood theatre the Balboa would in fact not be a venue for a Janus Films tribute this fall, knowing that the PFA is tackling two such series, one largely Europe-focused and the other Japanese is something of a balm. Just as enticing are the Jacques Rivette series, a set of Beat-era films, and a fascinating series guest-programmed by Akram Zaatari. And more. It almost makes me want to move to Berkeley.Adam Hartzell, who is currently in Busan, South Korea enjoying what is widely thought of as the best international film festival in Asia, the PIFF (and yes I'm extremely jealous that he gets to see stuff like Syndromes and a Century and Woman on the Beach and I don't), has been kind enough to let me publish a pair of reports on series devoted to documentarian artists-in-residence at the PFA. Here is a third one, on last month's resident Ali Kazimi. Adam:

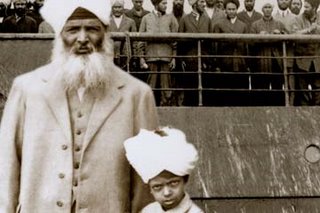

Thanks to funding by a grant from the Consortium for the Arts at UC Berkeley and presentation support by EKTA and 3rd I: South Asian Films, Indian-Canadian director Ali Kazimi came to town again, enabling Bay Area eyes their third chance to see Continuous Journey, a film which challenges the "liberal" history that is larger Canada's. In 1914, 376 citizens of the British Empire from British India sailed to Vancouver Bay on the Kamagata Maru. They should have been allowed entry onto the shores of Vancouver Bay since they were subjects of the King of England. But this was a year where Canadian pubs were rowdy with the chants of "White Canada Forever" and these subjects were denied entry. The hidden history that Continuous Journey reveals left an impact on me. Which is why I made the trek under the bay to the Pacific Film Archives to catch what I could of the rest of Kazimi's works. The other films and shorts screened in the weekend retrospective (September 14-16, 2006) demonstrated that Kazimi was not done teaching me.

Born and raised in Delhi, India Kazimi didn't grow up around "film", meaning the images shown on screens, but did grow up around film, that is, the material that enables those images to flicker on those very screens. His father worked for Kodak and the smells of chemicals and film stock still stimulate memory nodes of childhood in Kazimi as the smell of pine lumber brings back memories for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation (CBC) Indian-Canadian reporter in his documentary on Indian immigration in Canada. Although it makes sense that he would become a freelance photographer, Kazimi does not resign his path to that of a fated trajectory. He is well aware of all the work and risk required to bring him to where he is today. He taught himself photography from what was lying around his house rather than through mentored instruction. And his shift to film presents similar agency. While working on a marketing campaign in rural India to sell soft drinks, Kazimi asked his superior "Why?" That is, why were they selling hyper-sugar-ed drinks in an impoverished area where basic nutrients are commonly unavailable? A valid argument outside of standard business protocol. The "Why?" question was then thrown back at him, as in, 'Why are you here then?' Kazimi actively listened to this echo and changed the focus of his artistic lens towards film and radio projects. Kazimi would eventually realize that for him to make the films he really wanted to make, he had to leave India for Canada, where he found greater access to funding, intellectual freedom, and distribution, (although not a perfect scenario, as I will note later.)

'Who is speaking for whom?' is a constant question for Kazimi throughout his work. Although acknowledging the point can not be made without over-generalizing, he stated that upon coming to Canada he found the portrayals of people from the Indian subcontinent awash in stereotypes and other clichés and wanted to change that. Much of his work through the funding of the CBC and the National Film Board of Canada has enabled an opportunity to address these poorly painted pictures of a vast, diverse community. "Passage from India" was his contribution to a wider CBC series on the experiences of various Canadian immigrant communities. It follows a CBC newscaster who is the third descendent of Bagga Singh, one of the earliest Indian immigrants to Canada. The piece notes the Indian presence in the logging industry, placing Indians clearly within the iconic landscape that is Canada's symbol of herself.

And it is that landscape that follows Kazimi. Through the assistance of an interviewer's persistence to know whence Kazimi's ideas came, Kazimi realized he was searching for the answer to another question: How do people like him, relatively recent arrivals, fit into the Canadian landscape? He seems to have realized the answers to that question by emphasizing that all Indian immigrants to Canada will not "fit" the same way. In a piece about arranged marriages in the Indian-Canadian community entitled Some Kind of Arrangement, Kazimi follows three different Indian-Canadians from three different religious traditions: one Hindu, one Muslim, and one Sikh. Each has returned to the tradition of arranged marriages for a different reason. One subject comes to the arrangement quite quickly, at least in terms of physical presence. She only saw her future husband twice before their wedding week. Another subject comes from Marxist parents who met through falling in love rather than through arrangement. And another one comes from an ambiguous claim for "traditional" Indian values. Well-crafted and paced, this documentary allows for the emergence of the natural contradictions in our lives without appearing judgmental. The young Sikh-Canadian who longs for "traditional" values isn't able to explain in great depth what she means by "traditional". But when her arranged date demands he drive her car, she takes serious offence. These aren't moments to satisfy our sadistic chastising desires, but moments we can relate to, aware of our own trails as we try to negotiate romantic relationships that emerge through our familial, social, business, and computer networks. We might think we want one thing until the intersubjectivity with others causes us to adjust our categorization of our values so that they better explain ourselves to ourselves, let alone to others.Kazimi said he was reluctant to do Some Kind of Arrangement, and not just because such would require him to go against the informal pledge made amongst his fist-raised, filmmaking buddies to 'Never Make a Wedding Video!!!' He was primarily reluctant because he had deep-seated prejudices against the practice. But he presents three vastly divergent personal stories surrounding an issue that is most often lazily described as an archaic illegitimate practice. It was a woman I dated in college who pushed me beyond the lazy perspective I used to have on arranged marriages. She explained to me why she wasn't averse to taking her parents up on their offer to arrange a marriage for her within the Korean Seventh Day Adventist community. She had final veto on who would be eventually chosen and she trusted her parents enough to find someone in tune with what she wanted as a modern American woman. Although still not an arrangement I would choose, as notes one of the friends attending the arranged Hindi wedding in the documentary, 'Don't our friends and family arrange parties or other get togethers in hopes of assisting in their child's romantic union?' Yes, and the marriage-proposal newspapers of the Indian community have similarities to the Evangelical Christian ruse of eHarmony or the more democratic forum of Yahoo! Personals. So continues the paradox that it is amongst our differences that we find our similarities.

But there are certain practices to arranged marriages, such as the speed with which some happen and the unequal power dynamics often involved, that allow arranged marriages to be vulnerable to certain dangers. The trust required in the process can be more easily exploited by less than trustworthy folk. And it is this "darker side" of such marriages that Kazimi was equally reluctant to explore in Runaway Grooms. This documentary for the CBC brought Kazimi back to India to interview women who have been abandoned by their arranged husbands after these husbands and their complicit family members extorted as much dowry money and jewels from the arranged bride as they could. This abandonment is enabled by the men having Non-Resident-Indian (NRI) status that allows them to evade legal prosecution and direct moral consequence. Left in India with sympathetic biological families, cultural traditions make it difficult for these abandoned brides to remarry, to work, and to interact socially, while international political options benefiting their deadbeat husbands allows the husbands to petition for divorces once they've milked all the money they could out of their arranged spouses. Kazimi utilizes regular documentary tactics of narration and expert commentary to explain the tradition of the dowry and the options available, and not available, to these women and men and how economics and politics truly benefit the men. Although I'm sure Kazimi would still refuse to do a wedding video, the archival footage of both arranged marriages in this short allow for a tense, suspenseful structure of the narrative as we sit with the unease of the ceremony and speculate about the unease on the face of the soon-to-runaway first groom and the disgusting disinterest on the face of the second.

Kazimi uses the documentary form to demonstrate that these are not just personal choices and cultural practices, they are political in that the legal structure acts as an accomplice to the crimes of the 'runaway grooms'. Feminists are often portrayed falsely as 'man-haters' when they dare to shed light on these patriarchal elephants in our rooms. Kazimi's direction helps limit the justification (when there ever is one) for such weak reactive arguments against Feminisms by introducing us to some of the people who are seeking to remove these patriarchal parameters, some of whom are men. And returning to Kazimi's concern about how Indians are portrayed in the media, coupling Some Kind of Arrangement with Runaway Grooms at a single screening in this retrospective allows for a fuller picture of Indian cultures, emphasizing the plural. Kazimi demonstrates through both these pieces that he strives to show the complexity of the Indian diaspora, which includes the cultural practices that need to be supported and maintained, revisited and revised, or condemned and abolished.Kazimi carries this to portrayals of other cultures as well. His thesis film was a test of patience, patience with all the obstacles that come up when making a film, patience with the subject, and patience with himself. While doing research to find a topic for his thesis film, Kazimi came across the work of Iroquois photographer Jeffrey Thomas. Little did he know that a 12-year process was about to begin. The film, Shooting Indians, took that long to finish because Thomas had abandoned the project well before completion. (In the interim, Kazimi would go off to India to film Narmada: A Valley Rises about the activists who tried to stop the relocation of millions of Indian villagers to make way for the Narmada Valley Dam.) Kazimi was only able to return to the project when a chance meeting with Thomas's son enabled Kazimi and Thomas to reconnect. Thomas let Kazimi know that it was his own self-doubt that caused him to leave the project. But viewing the rough cuts of the earlier footage helped bring him back to the project. He remembered how he felt Kazimi was one of the few people he'd ever allow to follow him this intimately, because he felt he could relate to Kazimi as a fellow outsider within the Canadian landscape.

As the film demonstrates, it is difficult to talk about Jeffrey Thomas's photography without talking about Edward Curtis, the European-American photographer who made a name for himself taking portraits of his imagined images of what he felt Native Americans should look like. Thomas's initial approach to his work through Curtis's work is that of frustration when not outright anger. The communities Curtis visited were quite westernized when Curtis arrived, so Curtis staged many of the photographs to meet his required visions of how these Native Americans should look. In other words, they had to meet his stereotypes. Plus, Curtis followed a tradition of early ethnographers who came into indigenous communities, took what they wanted, but never returned to give anything back. The subjects of the photos were never paid and no photos were brought to them in return. In response to these images, Thomas's life's work was to represent the First Nations Peoples as they are now, not as they are imagined in Westerns or other iconic images controlled by institutions outside the First Nations community. One way Thomas controls the images is to place pictures of First Nations Peoples at various pow-wow events dressed up in traditional clothing amongst images of First Nations Peoples in their everyday clothing of jeans and t-shirts at the very same event. This disallows a static image of his people, demanding a more fluid, fluxing, non-stereotypical icon to emerge.

Shooting Indians had me thinking back to my first year in San Francisco when I attended an exhibition at the old Ansel Adams Photography Museum that used to be located on 4th Street between Folsom and Howard. Part of the exhibit was a series of photos of Native Americans taken by European-Americans juxtaposed against photos of Native Americans taken by Native Americans themselves. I have no way of confirming if these were images from the same exhibit curated by Jeffrey Thomas such as the one represented in this film, but I have a strong feeling what I witnessed back then was exactly that. That exhibit is partly responsible for why this Cleveland boy supports his hometown baseball team without displaying the racist Chief Wahoo emblem, instead wearing the cursive "I" used for holiday and Sunday home games. Kazimi helped me recover the memory of that exhibit that I hadn't purposely hidden, but hadn't recalled for some time.

And like my memory, Kazimi's filmmaking process has been anything but smooth. Although he has much praise for the National Film Board of Canada, an exemplary funding organization, and although he knows that his lot is better than his documentary-making friends in India, Kazimi still has run into his own problems. Distribution has been a particular burr in his side. The powers that slot documentaries on Canadian television wanted Kazimi to edit down Continuous Journey even though it was well within the usual length for films aired on the channel. Kazimi took this as an underhanded tactic to force him to get rid of the sobering portrayals of the less than honorable White Canadian populace of the time, portrayals to which some officials took offense. But the National Film Board of Canada provides its funding with flexible strings attached, so though he kept his film true to his vision, it was aired at an hour less hospitable to the average viewer.Besides these political and economic obstacles, there were the general obstacles of the filmmaking process. I've already mentioned how Kazimi was shooting Shooting Indians for 12 years due to the disappearance of his subject. Creating Continuous Journey had its own obstacles because there was very little archival footage from which to work. This required Kazimi to repeat images in his film more often than I'm sure he wanted. But his tireless archival work resulted in two choice finds that have strongly affected audiences. The first is the "White Canada Forever" popular pub song that shocks Canadian audiences when they hear it. Many Canadians have taken great pride, justifiably so, in thier progressive multicultural policies. But to discover this bit of hidden celebratory racism is quite a jolt to the national consciousness.

The second moment is the moving highpoint of moving images in Continuous Journey. It is the kind of surprise moment in a film I don't even want to reveal here in this non-review format where Spoiler!-warnings don't apply. I restrain myself because my hope is that readers will seek out their own chance to see this film. (It is available for purchase on his website.) Perhaps you will experience the same moment of cinematic awe that my fellow ticket-paying travelers did when we saw it together at the 2005 San Francisco Asian-American International Film Festival. Such are those collective connections one only has in the theatre, keeping us coming back again and again. But since this is likely to be a film not coming to a theatre near you, you'll have to settle for such an awe-full moment of an awful moment in Canada's history through the DVD format, the medium where this film's journey continues.