The 62st San Francisco International Film Festival is almost over; last night was the official "closing night" but repeat screenings continue today and Tuesday, April 23rd. Each day during the festival I've been posting about a festival selection I've seen or am anticipating.

|

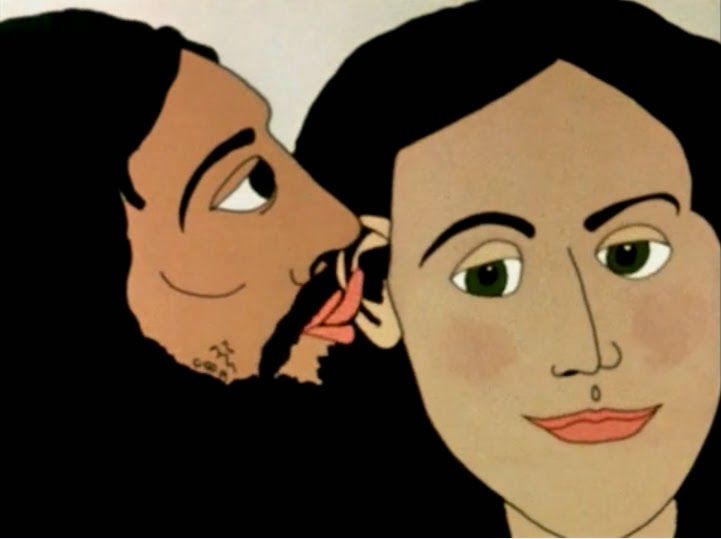

| A still from Laura Millán's The Labyrinth, playing at the 2019 San Francisco International Film Festival, April 10-23, 2019. Courtesy of SFFILM. |

playing: 6:00PM today at the Roxie, as part of the Shorts 5: New Visions program.

It could be a quirk of my own personal perception, but to me it feels like in the past few years the nation of Colombia has been undergoing an uptick in motion picture production and/or international distribution, possibly tied to the Foreign Language Oscar nomination of Ciro Guerra's Embrace of the Serpent from 2015. Guerra's follow-up (for the first time sharing co-directing credit with editor & producer Cristina Gallego) Birds of Passage became the first Latin American film ever to open the Director's Fortnight at Cannes last year, and showed at the Mill Valley Film Festival before a Frisco Bay commercial release earlier this year.

This year's SFFILM program boasts three Colombian productions or co-productions, as many as from any other majority-Spanish speaking country besides Mexico. Though the three screenings of the Vanguard selection Lapü have all passed, there's still one more festival screening of Monos, from the Dark Wave festival section, and The Labyrinth, one of the longest and most fascinating of the shorts in the New Visions program. It's an experimental documentary from a filmmaker associated with the Sensory Ethnography Lab that gave brought previous San Francisco International Film Festival audiences gems like Leviathan and Manakanama. The Labyrinth doesn't jump out at the viewer as akin to those highly-conceptual features, but rather uses a syncretic approach to materials that allow ideas to bury themselves into the viewer's mind, to be awakened at an unexpected future moment.

It's an oblique portrait of Medellín Cartel drug trafficker Evaristo Porras Ardila, who built a replica of the Carrington Family mansion from "Dynasty" in the Tres Fronteras region of the Amazon where Colombia's Southernmost point touches Peru and Brazil, as told by one of his Porras's former workers named Cristóbal Gómez. Huertas Millán combines a voiceover from Gómez with intercut images of the ruin of the real, recreated mansion and the original, patchworked mansion as filmed by Emmy-nominated cinematographer Michel Hugo (and/or his fellow "Dynasty" DPs). The ruin images feel straight out of a visit to Angkor Wat or another truly ancient fallen city, and when contrasted against televised icons of Reagan-era wealth feel like the rotting interior of an entire economic system. The latter half of The Labyrinth makes more mystical turns into the connections between the jungle and states of altered consciousness. It's a powerful work that was justly praised on its tour of major experimental film festival showcases such as Locarno, Toronto's Wavelengths, the New York Film Festival's Projections, etc.

The Labyrinth is joined by a selection of moving image works by underground artists from around the world in the New Visions program. More than one also contrast mediated televisual images with more personal footage to provocative effect: Akosua Adoma Owusu's Pelourinho, They Don’t Really Care About Us is a Ghanaian maker's look at another South American country, bringing into her 16mm film world both a 1926 letter from W.E.B. DuBois to the Brazilian president and shots from Spike Lee's music video for a Michael Jackson song (the same one also featured prominently in a scene in another SFFILM selection, now a Golden Gate Award winner, Midnight Traveler) shot in the favelas of Rio. The critic Neil Young has written extensively and passionately about this piece. Another similar hybrid is local filmmaker Sandra Davis's That Woman, which intercuts the 1999 ABC broadcast of Barbara Walters interviewing Monica Lewinsky (complete with late-breaking interjections of news about the death of Stanley Kubrick) with scenes of a re-enactment shot in the San Francisco Art Institute's Studio 8, with George Kuchar as Walters interviewing a Lewinsky look-alike. Given that Kuchar died over seven and a half years ago, I understand why Jonathan Marlow followed an impulse to list it in my blog's repertory round-up; he notes that it was "recently completed" by Davis (its local premiere was last summer at 16 Sherman Street) but the presence in the cast of a man who died (too young) over seven and a half years ago makes it feel older than its completion date suggests. Yet now seems like the perfect moment to release a short that would have taken on very different resonances two or three or ten or fifteen years ago. (I don't know if it was shot that long ago; it could've been anywhere from 1999 to 2011 by my initial reckoning).

Add in strong work like Zachary Epcar's Life After Love, Courtney Stephens' Mixed Signals, Sun Kim's Now and Here, Here and Then and Ariana Gerstein's Traces with Elikem, and this is the strongest New Visions program I've seen at SFFILM in several years. Perhaps that's only sensible in the first year in the past quarter-century that the festival has cut its presentation of new experimental shorts from two programs down to one, as I discussed last week, but I wouldn't want to read too much into it. Perhaps it's just a program more aligned with my own personal taste. Which is why I was surprised to see that the Golden Gate Awards shorts jury decided to go outside of the New Visions category to award the festival's $2,000 cash prize for a New Visions work to a short that had been placed in the Animated Short category: Urszula Palusińska's Cold Pudding Settles Love. Definitely one of the stranger entrants in the Animated Shorts competition, it is hard to compare against a crowd-pleasing laugh machine like Claudius Gentinetta's Selfies, which won the Animated Short GGA. While I don't know if the jury's category-confounding selection is unprecedented for the Golden Gate Awards, it's certainly unusual. It makes me glad that The Labyrinth as well as Epcar's Life After Love and Stephens' Mixed Signals will at least get another chance to screen for Frisco Bay audiences during the June 7-9 Crossroads Festival held by SF Cinematheque at SFMOMA and just announced this morning. I'm not sure if that festival still has an audience award prize, and if so I'm certain it's not going to come with $2000, but at the very minimum these films can extend their reach to more viewers.

SFFILM62 Day 13

Other festival options: With just two more days in the festival, everything is now down to it's final screening, so today's your last festival chance to see anything that happens to be playing. I can recommend The Load, which I wrote about yesterday, most highly (it plays the Victoria at 3:30PM), and Jennifer Kent's The Nightingale with some major reservations, not so much regarding its brutal violence (although if you don't want to watch that I certainly don't blame you), but the moments near the end of the film that strain credulity after the believably bleak outlook adopted from the early scenes. That one screens at the Roxie at 8:30PM.

Non-SFFILM option: The Castro Theatre (which incidentally has a good portion of its May offerings on its website, including a day-long screening of a new DCP of Sergei Bondarchuk's 7-hour War & Peace May 25) tonight launches a pretty cinephile-friendly final week and change before the San Francisco Silent Film Festival opens May 1st. Tonight's World War I-themed double-bill pairs a 35mm print of Peter Weir's rarely-revived 1981 classic Gallipoli with a 3D presentation of Peter Jackson's recent documentary They Shall Not Grow Old. Other 35mm prints playing there this week include Joseph Losey's Boom!, David Lynch's Mulholland Dr., and a day stuffed with films starring Italian actor Ugo Tognazzi, including films by auteurs Elio Petri, Bernardo Bertolucci, Dino Risi and Marco Ferreri, all presented in prints brought in by the Italian Cultural Institute.